Nelligan O’Brien Payne gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Rachelle Bastarache, Student-at-Law in writing this blog post.

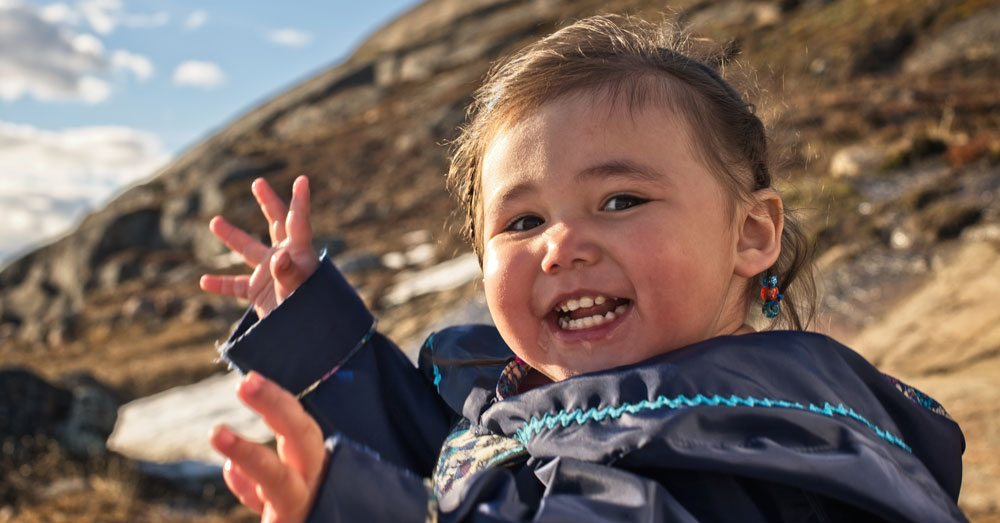

Understanding their heritage and cultural identity is a vital part of a child’s upbringing. It is particularly important for Indigenous people in Canada, who historically have fought hard to preserve their heritage and identity.

However, only months after Ontario voted to adopt sweeping changes to the child protection and public adoption regime to take into account unique Indigenous relationships, a decision by the British Columbia Court of Appeal makes one wonder just how meaningful this reform will be in Ontario.

However, only months after Ontario voted to adopt sweeping changes to the child protection and public adoption regime to take into account unique Indigenous relationships, a decision by the British Columbia Court of Appeal makes one wonder just how meaningful this reform will be in Ontario.

Bill 89

On June 1, 2017, the Ontario government passed Bill 89, which will repeal the current Child and Family Services Act and replace it with the Child, Youth and Family Services Act, 2017. The new legislation, which will come into force in the Spring of 2018, aims to better represent Indigenous voices in the child protection and adoption regime.

However, the incoming legislation appears to fall short of this goal.

Similar to the current legislation, the new legislation mandates the court to consider the importance of preserving culture, traditions and heritage when determining the best interests of First Nations, Inuk or Métis children in child protection and adoption proceedings.

What the incoming legislation fails to do is give this factor any elevated status in comparison to other factors a court must consider when determining an Indigenous child’s best interests.

M.M. v. T.B.

In a unanimous decision last month, M.M. v. T.B., the British Columbia Court of Appeal considered legislation similar to that of Ontario and concluded that if the British Columbia legislature intended for Aboriginal heritage and cultural identity to attract a “super weight” over all other factors when determining an adoption order, it would have said so. Instead, it held that the weight a judge attaches to preserving a child’s Aboriginal heritage and culture is an exercise of discretion, to be considered with all other factors enumerated in the legislation.

This is in contrast to legislation in Nova Scotia, the Children and Family Services Act, which the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal has said grants “super weight” to placing a child with a family that is compatible with that child’s cultural, racial or linguistic heritage, when possible.

What should Ontario have done?

If the Legislative Assembly in Ontario truly wanted a paradigm shift, it would have granted a strict directive to give the preservation of Indigenous culture “super weight”, unless specific circumstances dictated otherwise. Instead, it appears the legislature chose to simply pay lip service to Indigenous culture rather than engage in meaningful action.

In the spirit of reconciliation and clearer hindsight vision, Ontario can do better.

For more information on child protection, adoption and a child’s best interest, contact our Family Law Group.